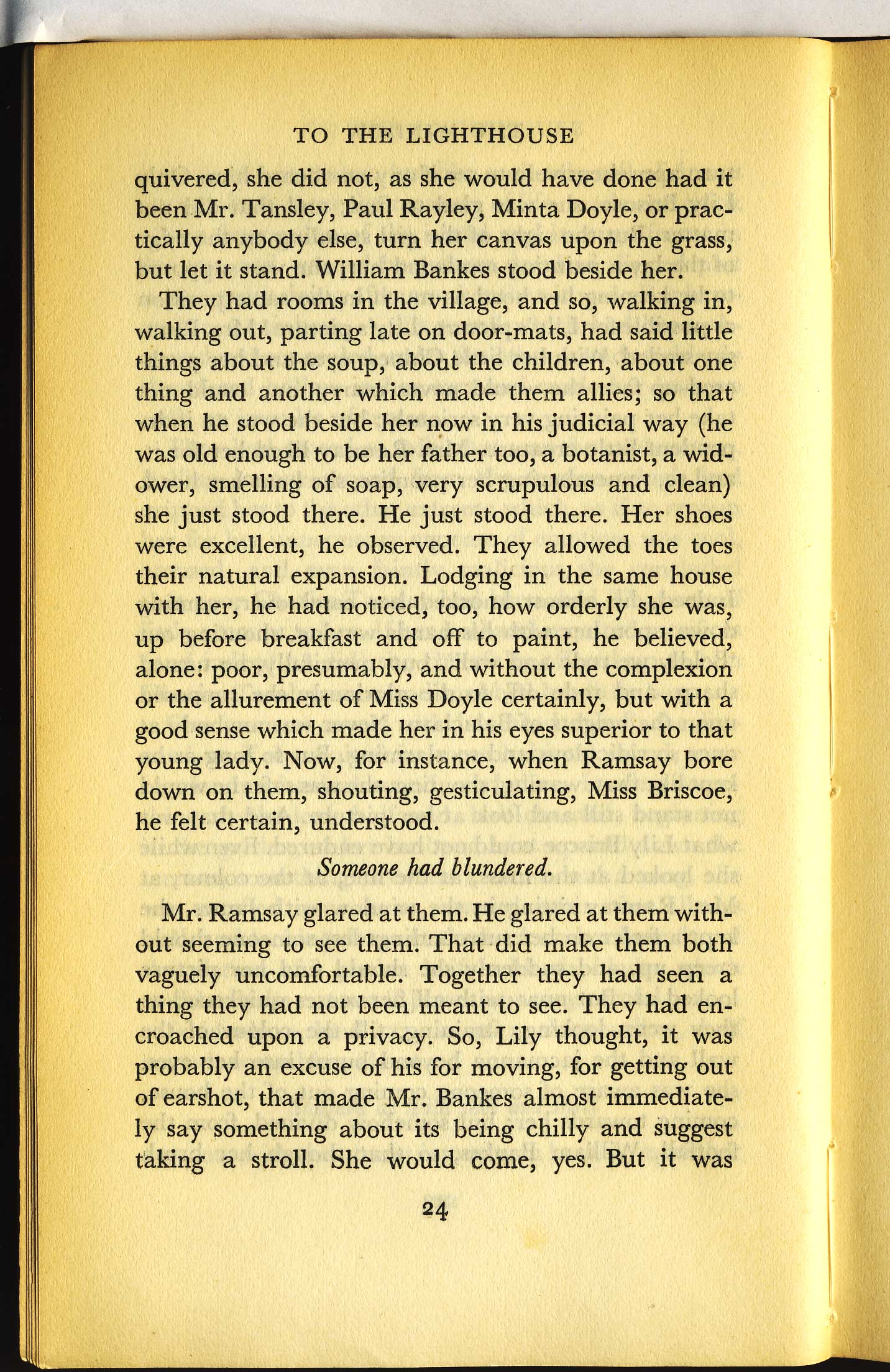

TO THE LIGHTHOUSEquivered, she did not, as she would have done had itbeen Mr. Tansley, Paul Rayley, Minta Doyle, or prac-tically anybody else, turn her canvas upon the grass,but let it stand. William Bankes stood beside her.They had rooms in the village, and so, walking in,walking out, parting late on door-mats, had said littlethings about the soup, about the children, about onething and another which made them allies; so thatwhen he stood beside her now in his judicial way (hewas old enough to be her father too, a botanist, a wid-ower, smelling of soap, very scrupulous and clean)she just stood there. He just stood there. Her shoeswere excellent, he observed. They allowed the toestheir natural expansion. Lodging in the same housewith her, he had noticed, too, how orderly she was,up before breakfast and off to paint, he believed,alone: poor, presumably, and without the complexionor the allurement of Miss Doyle certainly, but with agood sense which made her in his eyes superior to thatyoung lady. Now, for instance, when Ramsay boredown on them, shouting, gesticulating, Miss Briscoe,he felt certain, understood.Someone had blundered.Mr. Ramsay glared at them. He glared at them with-out seeming to see them. That did make them bothvaguely uncomfortable. Together they had seen athing they had not been meant to see. They had en-croached upon a privacy. So, Lily thought, it wasprobably an excuse of his for moving, for getting outof earshot, that made Mr. Bankes almost immediate-ly say something about its being chilly and suggesttaking a stroll. She would come, yes. But it was24

Resize Images

Select Pane

Berg Materials

- 1. Notebook I Cover

- 2. F3 / P1

- 3. F5 / P2

- 4. F7 / P3

- 5. F9 / P4

- 6. F11 / P5

- 7. F13 / P6

- 8. F15 / P7

- 9. F17 / P8

- 10. F19 / P9

- 11. F21 / P10

- 12. F23 / P11

- 13. F25 / P12

- 14. verso of Berg F25

- 15. F27 / P13

- 16. F29 / P14

- 17. F31; P15

- 18. F33 / P16

- 19. F35 / P17

- 20. F37 / P18

- 21. F39 / P19

- 22. F41 / P20

- 23. F43 / P21

- 24. F45 / P22

- 25. F47 / P23

- 26. F49 / P24

- 27. F51 / P25

- 28. F53 / P26

- 29. F55 / P27

- 30. F57 / P28

- 31. F59 / P29

- 32. F61 / P30

- 33. F61 / P30 verso

- 34. F63 / P31

- 35. F65 / P32

- 36. F67 / P33

- 37. F69 / P34

- 38. F71 / P35

- 39. verso F71

- 40. F73 / P36

- 41. F75 / P37

- 42. F77 / P38

- 43. F79 / P39

- 44. F81 / P40

- 45. F91 / P45

- 46. F93 / P46

- 47. F95 / P47

- 48. F97 / P48

- 49. F99 / P49

- 50. F101 / P50

- 51. F103 / P51

- 52. F105 / P52

- 53. F107 / P53

- 54. F109 / P54

- 55. F111 / P55

- 56. F113 / P56

- 57. F115 / P57

- 58. F117 / P58

- 59. F119 / P59

- 60. verso F119

- 61. F121 / P60

- 62. F123 / P61

- 63. F125 / P62

- 64. F127 / P63

- 65. F129 / P64

- 66. F131 / P65

- 67. F133 / P66

- 68. F135 / P67

- 69. F137 / P68

- 70. F139 / P69

- 71. F139 / P69 verso

- 72. F141 / P70

- 73. F143 / P71

- 74. F145 / P72

- 75. F147 / P73

- 76. Fol. 149 / P74

- 77. F151 / P75

- 78. F153 / P76

- 79. F155 / P77

- 80. F157 / P78

- 81. F159 / P79

- 82. F161 / P80

- 83. F163 / P81

- 84. F167 / P82

- 85. 167 / P82 verso

- 86. F169 / P83

- 87. F171 / P84

- 88. F173 / P85

- 89. F175 / P86

- 90. F177 / P87

- 91. F179 / P88

- 92. F181 / P89

- 93. F183 / P90

- 94. F185 / P91

- 95. F187 / P92

- 96. F189 / P93

- 97. F191 / P94

- 98. F193 / P95

- 99. F195 / P96

- 100. F197 / P97

- 101. F197 / P97 verso

- 102. F199 / P98

- 103. F199 / P98 verso

- 104. F201 / P99

- 105. F203 / P100

- 106. F205 / P101

- 107. F207 / P102

- 108. F207 / 102 verso

- 109. F209 / P103

- 110. F211 / P104

- 111. F213 / P105

- 112. F215 / P106

- 113. F217 / P107

- 114. F219 / P108

- 115. F221 / P109

- 116. F223 / P110

- 117. F225 / P111

- 118. F227 / P112

- 119. F229 / P113

- 120. F231 / P114

- 121. F233 / P115

- 122. F235 / P116

- 123. F237 / P117

- 124. F239 / P118

- 125. F241 / P119

- 126. F243 / P120

- 127. F245 / P121

- 128. F247 / P122

- 129. F249 / P123

- 130. F251 / P124

- 131. F251 / P124 verso

- 132. F253 / P125

- 133. F255 / P126

- 134. F257 / P127

- 135. F259 / P128

- 136. F261 / P129

- 137. F263 / P130

- 138. F265 / P131

- 139. F267 / P132

- 140. F269 / P133

- 141. F271 / P134

- 142. F273 / P135

- 143. F275 / P136

- 144. F277 / P137

- 145. F279 / P138

- 146. F281 / P139

- 147. F283 / P140

- 148. F285 / P141

- 149. F287 / P142

- 150. F289 / P143

- 151. F291 / P144

- 152. F293 / P145

- 153. F295 / P146

- 154. F297 / P147

- 155. F299 / P148

- 156. F301 / P149

- 157. F303 / P150

- 158. F305 / P151

- 159. F307 / P152

- 160. F309 / P153

- 161. F311/ P154

- 162. F313 / P155

- 163. 156 verso

- 164. 157 verso

- 165. 158 verso

- 166. Notebook I Rear Cover

- 167. Notebook II Cover

- 168. N2F1 / P159

- 169. N2F3 / P160

- 170. N2F5 / P161

- 171. N2F7 / P162

- 172. N2F9 / P163

- 173. N2F11 / P164

- 174. N2F13 / P165

- 175. N2F15 / P166

- 176. N2F17 / P167

- 177. N2F19 / P168

- 178. N2F21 / P169

- 179. N2F23 / P170

- 180. N2F25 / P171

- 181. N2F27 /P172

- 182. N2F29 / P173

- 183. N2F31 / P174

- 184. N2F33 / P175

- 185. N2F35 / P176

- 186. N2F37 / P177

- 187. N2F39 / P178

- 188. N2F41 / P179

- 189. N2F43 / P180

- 190. N2F45 / P181

- 191. N2F47 / P182

- 192. N2F49 / P183

- 193. N2F51 / P184

- 194. Notebook II Rear Cover

- 195. Notebook III Cover

- 196. N3F1 / P185

- 197. N3F[3] / F138 / P186

- 198. N3F5 / F139 / P187

- 199. N3F7 / F140 / P188

- 200. N3F9 / F141 / P189

- 201. N3F11 / F142 / P190

- 202. N3F13 / F142 / P191

- 203. N3F15 / F143 / P192

- 204. N3F17 / F144 / P193

- 205. N3F19 / F145 / P194

- 206. N3F21 / F146 / P195

- 207. N3F23 / F147 / P196

- 208. N3F25 / F148 / P197

- 209. N3F27 / F149 / P198

- 210. N3F29 / F150 / P199

- 211. N3F31 / F151 / P200

- 212. N3F33 / F152 / P201

- 213. N3F35 / F153 / P202

- 214. N3F37 / F154 / P203

- 215. N3F39 / F155 / P204

- 216. N3F41 / F156 / P205

- 217. verso of VW P156

- 218. N3F43 / F157 / P206

- 219. N3F45 / F158 / P207

- 220. N3F47 / F159 / P208

- 221. N3F49 / F160 / P209

- 222. N3F51 / F161 / P210

- 223. N3F53 / F162 / P211

- 224. N3F55 / F163 / P212

- 225. N3F57 / F164 / P213

- 226. N3F59 / F165 / P214

- 227. N3F61/ F166 / P215

- 228. N3F63 / F167 / P216

- 229. F63 / P216 verso

- 230. NF65 / F168 / P217

- 231. N3F67 / F169 / P218

- 232. N3F69 / F170 / P219

- 233. 219 verso

- 234. N3F71 / F171 / P220

- 235. N3F73 / F172 / P221

- 236. N3F75 / F173 / P222

- 237. N3F77 / F174 / P223

- 238. N3F79 / F175 / P224

- 239. N3F81 / F176 / P225

- 240. 225 verso

- 241. N3F83 / F177 / P226

- 242. N3F85 / F178 / P227

- 243. N3F87 / F179 / P228

- 244. N3F89 / F180 / P229

- 245. 229 verso

- 246. N3F91 / F181 / P230

- 247. N3F93 / F182 / P231

- 248. N3F95 / F183 / P232

- 249. N3F97 / F184 / P233

- 250. F99 / P234

- 251. N3F101 / F185 / P235

- 252. N3F103 / F186 / P236

- 253. N3F105 / F187 / P237

- 254. N3F107 / F188 / P238

- 255. N3F109 / F189 / P239

- 256. N3F111 / F190 / P240

- 257. N3F113 / F191 / P241

- 258. N3F115 / F192 / P242

- 259. N3F117 / F193 / P243

- 260. N3F119 / F194 / P244

- 261. N3F121 / F195 / P245

- 262. N3F123 / F196 / P246

- 263. N3F125 / F197 / P247

- 264. N3F127 / F198 / P248

- 265. N3F129 / F199 / P249

- 266. N3F131 / F200 / P250

- 267. N3F133 / F202 / P251

- 268. NF135 / F203 / P252

- 269. N3F137 / F204 / P253

- 270. N3F139 / F205 / P254

- 271. N3F141 / F206 / P255

- 272. N3F143 / F205 / P256

- 273. N3F145 / F206 / P257

- 274. N3F147 / F207 / P258

- 275. N3F149 / F208 / P259

- 276. N3F151 / F209 / P260

- 277. N3F151 / P260 verso

- 278. N3F153 / F210 / P261

- 279. N3F155 / F211 / P262

- 280. N3F157 / F212 / P263

- 281. N3F159 / F213 / P264

- 282. N3F161 / F214 / P265

- 283. F161 / P265 verso

- 284. N3F163 / F215 / P266

- 285. N3F165 / F216 / P267

- 286. N3F167 / F217 / P268

- 287. N3F169 / N218 / P269

- 288. N3F170 / P269 verso

- 289. N3F171 / F219 / P270

- 290. N3F173 / F220 / P271

- 291. N3F175 / F221 / P272

- 292. N3F177 / F222 / P273

- 293. N3F179 / F223 / P274

- 294. N3F181 / F224 / P275

- 295. N3F183 / F225 / P276

- 296. N3F185 / F226 / P277

- 297. N3F187 / F227 / P278

- 298. N3F189 / F228 / P279

- 299. N3F191 / F229 / P280

- 300. N3F193 / F230 / P281

- 301. N3F195 / F231 / P282

- 302. N3F197 / F202 / P283

- 303. N3F199 / F203 / P284

- 304. N3F201 / P285

- 305. N5F203 / F205 / P286

- 306. N3F205 / F206 / P287

- 307. N3F207 / F207 / P288

- 308. N3F209 / F208 / P289

- 309. N3F211 / F209 / P290

- 310. N3F213 / F210 / P291

- 311. N3F215 / F211 / P292

- 312. N3F217 / F212 / P293

- 313. N3F219 / F213 / P294

- 314. N3F221 / F214 / P295

- 315. N3F223 / F215 / P296

- 316. N3F225 / F216 / P297

- 317. N3F227 / F217 / P298

- 318. N3F229 / F218 / P299

- 319. N3F231 / F219 / P300

- 320. N3F233 / F220 / P301

- 321. N3F235 / F221 / P302

- 322. N3F237 / F222 / P303

- 323. N3F239 / F223 / P304

- 324. N3F241 / F224 / P305

- 325. N3F243 / F225 / P306

- 326. N3F245 / F226 / P307

- 327. N3F245 / P307 verso

- 328. N3F247 / F227 / P308

- 329. N3F249 / F228 / P309

- 330. N3F251 / F229 / P310

- 331. N3F253 / F230 / P311

- 332. N3F255 / F232 / P312

- 333. N3F257 / F233 / P313

- 334. N3F249 / F234 / P314

- 335. N3F251 / F235 / P315

- 336. N3F253 / F236 / P316

- 337. N3F255 / F237 / P317

- 338. N3F257 / F238 / P318

- 339. N3F259 / F239 / P319

- 340. N3F261 / F240 / P320

- 341. N3F263 / F241 / P321

- 342. N3F265 / F242 / P322

- 343. N3F267 / F243 / P323

- 344. F267 / P323 verso

- 345. N3F269 / F244 / P324

- 346. N3F271 / F245 / P325

- 347. N3F273 / F246 / P326

- 348. N3F275 / F247 / P327

- 349. N3F275 / P327 verso

- 350. N3F277 / F248 / P328

- 351. N3F279 / F249 / P329

- 352. N3F281 / F250 / P330

- 353. N3F283 / F251 / P331

- 354. N3F285 / F251 / P332

- 355. N3F287 / F252 / P333

- 356. N3F289 / F253 / P334

- 357. N3F291 / F254 / P335

- 358. N3F241 / P335 verso

- 359. N3F293 / F255 / Appendix C.336

- 360. N3F295 / F256 / P337

- 361. N3F297 / F257 / P338

- 362. N3F299 / F258 / P339

- 363. N3F301 / F258 / P340

- 364. N3F303 / F259 / P341

- 365. N3F305 / F260 / P342

- 366. N3F307 / F261 / P343

- 367. N3F309 / F262 / P344

- 368. N3F309 /P344 verso

- 369. N3F311 / F263 / P345

- 370. N3F313 / F264 / P346

- 371. N3F315 / F265 / P347

- 372. N3F317 / F266 / P348

- 373. N3F319 / F267 / P349

- 374. N3F321 / F268 / P350

- 375. N3F323 / F269 / P351

- 376. N3F325 / F270 / P352

- 377. N3F271 / P353

- 378. N3F327 / F1 / P354

- 379. N3F329 /P355

- 380. N3F331 / P356

- 381. N3F333 / P357

- 382. N3F335 / P358

- 383. N3F337 / P359

- 384. N3F339 / P360

- 385. N3F253 / verso Berg pg 339

- 386. N3F341 / P361

- 387. N3F343 / P362

- 388. N3F345 / P363

- 389. N3F347 / P364

- 390. N3F349 / P365

- 391. N3F351 / P366

- 392. Appendix A/7

- 393. Appendix A/8

- 394. Appendix A/9

- 395. Appendix A/10

- 396. Appendix A/11

- 397. Appendix A/12

- 398. Appendix A/13

- 399. C/41

- 400. C/42

- 401. C/43

- 402. C/44

- 403. C/156 verso

- 404. C/157 verso

- 405. C/336

- 406. Appendix B

- 407. Albatross Agreement

- 408. DIAL advert