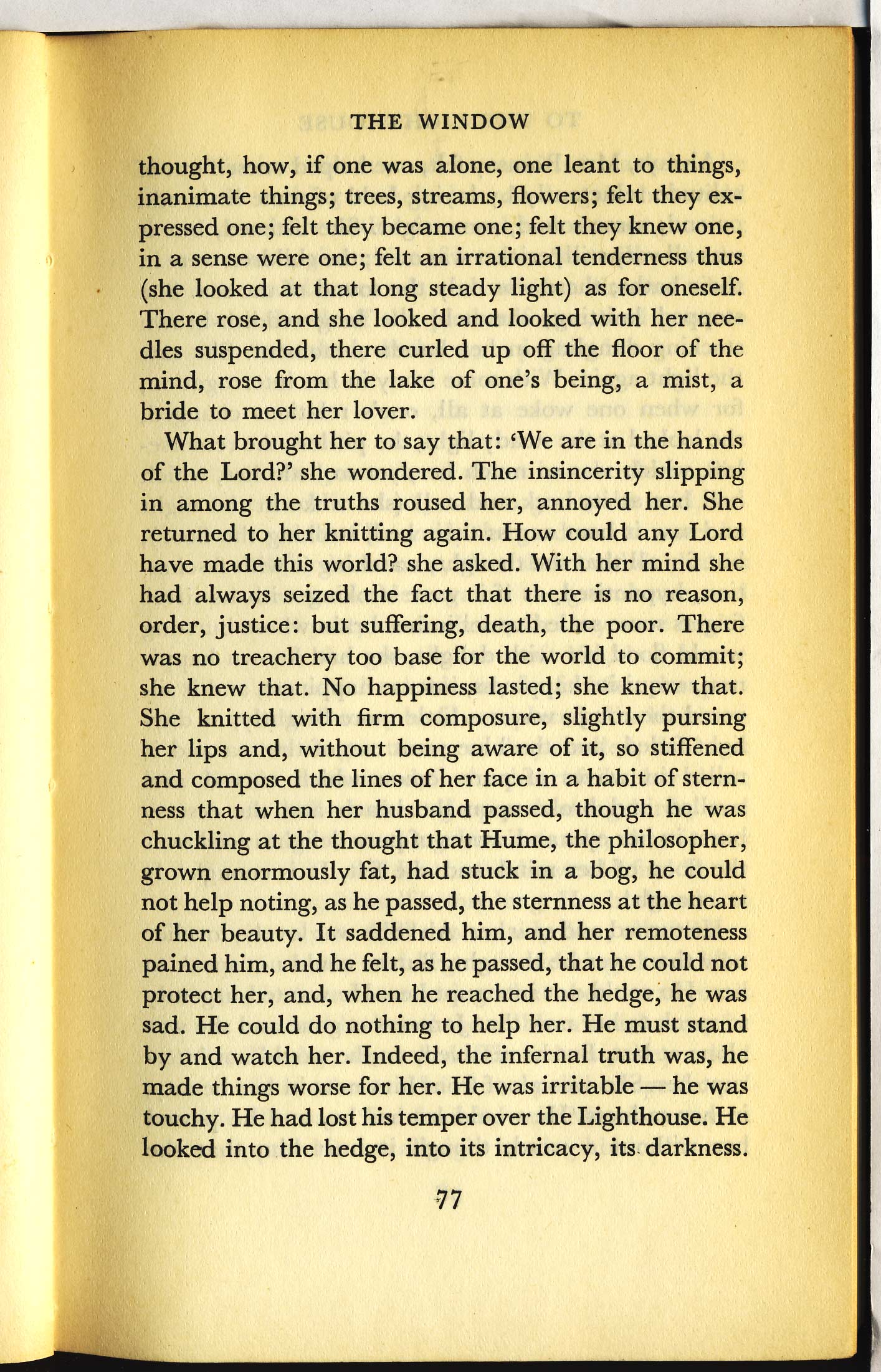

What brought her to say that: ŌĆśWe are in the handsof the Lord?ŌĆÖ she wondered. The insincerity slippingin among the truths roused her, annoyed her. Shereturned to her knitting again. How could any Lordhave made this world? she asked. With her mind shehad always seized the fact that there is no reason,order, justice: but suffering, death, the poor. Therewas no treachery too base for the world to commit;she knew that. No happiness lasted; she knew that.She knitted with firm composure, slightly pursingher lips and, without being aware of it, so stiffenedand composed the lines of her face in a habit of stern-ness that when her husband passed, though he waschuckling at the thought that Hume, the philosopher,grown enormously fat, had stuck in a bog, he couldnot help noting, as he passed, the sternness at the heartof her beauty. It saddened him, and her remotenesspained him, and he felt, as he passed, that he could notprotect her, and, when he reached the hedge, he wassad. He could do nothing to help her. He must standby and watch her. Indeed, the infernal truth was, hemade things worse for her. He was irritable ŌĆö he wastouchy. He had lost his temper over the Lighthouse. Helooked into the hedge, into its intricacy, its darkness.77

Select Pane

Berg Materials

- 1. Notebook I Cover

- 2. F3 / P1

- 3. F5 / P2

- 4. F7 / P3

- 5. F9 / P4

- 6. F11 / P5

- 7. F13 / P6

- 8. F15 / P7

- 9. F17 / P8

- 10. F19 / P9

- 11. F21 / P10

- 12. F23 / P11

- 13. F25 / P12

- 14. verso of Berg F25

- 15. F27 / P13

- 16. F29 / P14

- 17. F31; P15

- 18. F33 / P16

- 19. F35 / P17

- 20. F37 / P18

- 21. F39 / P19

- 22. F41 / P20

- 23. F43 / P21

- 24. F45 / P22

- 25. F47 / P23

- 26. F49 / P24

- 27. F51 / P25

- 28. F53 / P26

- 29. F55 / P27

- 30. F57 / P28

- 31. F59 / P29

- 32. F61 / P30

- 33. F61 / P30 verso

- 34. F63 / P31

- 35. F65 / P32

- 36. F67 / P33

- 37. F69 / P34

- 38. F71 / P35

- 39. verso F71

- 40. F73 / P36

- 41. F75 / P37

- 42. F77 / P38

- 43. F79 / P39

- 44. F81 / P40

- 45. F91 / P45

- 46. F93 / P46

- 47. F95 / P47

- 48. F97 / P48

- 49. F99 / P49

- 50. F101 / P50

- 51. F103 / P51

- 52. F105 / P52

- 53. F107 / P53

- 54. F109 / P54

- 55. F111 / P55

- 56. F113 / P56

- 57. F115 / P57

- 58. F117 / P58

- 59. F119 / P59

- 60. verso F119

- 61. F121 / P60

- 62. F123 / P61

- 63. F125 / P62

- 64. F127 / P63

- 65. F129 / P64

- 66. F131 / P65

- 67. F133 / P66

- 68. F135 / P67

- 69. F137 / P68

- 70. F139 / P69

- 71. F139 / P69 verso

- 72. F141 / P70

- 73. F143 / P71

- 74. F145 / P72

- 75. F147 / P73

- 76. Fol. 149 / P74

- 77. F151 / P75

- 78. F153 / P76

- 79. F155 / P77

- 80. F157 / P78

- 81. F159 / P79

- 82. F161 / P80

- 83. F163 / P81

- 84. F167 / P82

- 85. 167 / P82 verso

- 86. F169 / P83

- 87. F171 / P84

- 88. F173 / P85

- 89. F175 / P86

- 90. F177 / P87

- 91. F179 / P88

- 92. F181 / P89

- 93. F183 / P90

- 94. F185 / P91

- 95. F187 / P92

- 96. F189 / P93

- 97. F191 / P94

- 98. F193 / P95

- 99. F195 / P96

- 100. F197 / P97

- 101. F197 / P97 verso

- 102. F199 / P98

- 103. F199 / P98 verso

- 104. F201 / P99

- 105. F203 / P100

- 106. F205 / P101

- 107. F207 / P102

- 108. F207 / 102 verso

- 109. F209 / P103

- 110. F211 / P104

- 111. F213 / P105

- 112. F215 / P106

- 113. F217 / P107

- 114. F219 / P108

- 115. F221 / P109

- 116. F223 / P110

- 117. F225 / P111

- 118. F227 / P112

- 119. F229 / P113

- 120. F231 / P114

- 121. F233 / P115

- 122. F235 / P116

- 123. F237 / P117

- 124. F239 / P118

- 125. F241 / P119

- 126. F243 / P120

- 127. F245 / P121

- 128. F247 / P122

- 129. F249 / P123

- 130. F251 / P124

- 131. F251 / P124 verso

- 132. F253 / P125

- 133. F255 / P126

- 134. F257 / P127

- 135. F259 / P128

- 136. F261 / P129

- 137. F263 / P130

- 138. F265 / P131

- 139. F267 / P132

- 140. F269 / P133

- 141. F271 / P134

- 142. F273 / P135

- 143. F275 / P136

- 144. F277 / P137

- 145. F279 / P138

- 146. F281 / P139

- 147. F283 / P140

- 148. F285 / P141

- 149. F287 / P142

- 150. F289 / P143

- 151. F291 / P144

- 152. F293 / P145

- 153. F295 / P146

- 154. F297 / P147

- 155. F299 / P148

- 156. F301 / P149

- 157. F303 / P150

- 158. F305 / P151

- 159. F307 / P152

- 160. F309 / P153

- 161. F311/ P154

- 162. F313 / P155

- 163. 156 verso

- 164. 157 verso

- 165. 158 verso

- 166. Notebook I Rear Cover

- 167. Notebook II Cover

- 168. N2F1 / P159

- 169. N2F3 / P160

- 170. N2F5 / P161

- 171. N2F7 / P162

- 172. N2F9 / P163

- 173. N2F11 / P164

- 174. N2F13 / P165

- 175. N2F15 / P166

- 176. N2F17 / P167

- 177. N2F19 / P168

- 178. N2F21 / P169

- 179. N2F23 / P170

- 180. N2F25 / P171

- 181. N2F27 /P172

- 182. N2F29 / P173

- 183. N2F31 / P174

- 184. N2F33 / P175

- 185. N2F35 / P176

- 186. N2F37 / P177

- 187. N2F39 / P178

- 188. N2F41 / P179

- 189. N2F43 / P180

- 190. N2F45 / P181

- 191. N2F47 / P182

- 192. N2F49 / P183

- 193. N2F51 / P184

- 194. Notebook II Rear Cover

- 195. Notebook III Cover

- 196. N3F1 / P185

- 197. N3F[3] / F138 / P186

- 198. N3F5 / F139 / P187

- 199. N3F7 / F140 / P188

- 200. N3F9 / F141 / P189

- 201. N3F11 / F142 / P190

- 202. N3F13 / F142 / P191

- 203. N3F15 / F143 / P192

- 204. N3F17 / F144 / P193

- 205. N3F19 / F145 / P194

- 206. N3F21 / F146 / P195

- 207. N3F23 / F147 / P196

- 208. N3F25 / F148 / P197

- 209. N3F27 / F149 / P198

- 210. N3F29 / F150 / P199

- 211. N3F31 / F151 / P200

- 212. N3F33 / F152 / P201

- 213. N3F35 / F153 / P202

- 214. N3F37 / F154 / P203

- 215. N3F39 / F155 / P204

- 216. N3F41 / F156 / P205

- 217. verso of VW P156

- 218. N3F43 / F157 / P206

- 219. N3F45 / F158 / P207

- 220. N3F47 / F159 / P208

- 221. N3F49 / F160 / P209

- 222. N3F51 / F161 / P210

- 223. N3F53 / F162 / P211

- 224. N3F55 / F163 / P212

- 225. N3F57 / F164 / P213

- 226. N3F59 / F165 / P214

- 227. N3F61/ F166 / P215

- 228. N3F63 / F167 / P216

- 229. F63 / P216 verso

- 230. NF65 / F168 / P217

- 231. N3F67 / F169 / P218

- 232. N3F69 / F170 / P219

- 233. 219 verso

- 234. N3F71 / F171 / P220

- 235. N3F73 / F172 / P221

- 236. N3F75 / F173 / P222

- 237. N3F77 / F174 / P223

- 238. N3F79 / F175 / P224

- 239. N3F81 / F176 / P225

- 240. 225 verso

- 241. N3F83 / F177 / P226

- 242. N3F85 / F178 / P227

- 243. N3F87 / F179 / P228

- 244. N3F89 / F180 / P229

- 245. 229 verso

- 246. N3F91 / F181 / P230

- 247. N3F93 / F182 / P231

- 248. N3F95 / F183 / P232

- 249. N3F97 / F184 / P233

- 250. F99 / P234

- 251. N3F101 / F185 / P235

- 252. N3F103 / F186 / P236

- 253. N3F105 / F187 / P237

- 254. N3F107 / F188 / P238

- 255. N3F109 / F189 / P239

- 256. N3F111 / F190 / P240

- 257. N3F113 / F191 / P241

- 258. N3F115 / F192 / P242

- 259. N3F117 / F193 / P243

- 260. N3F119 / F194 / P244

- 261. N3F121 / F195 / P245

- 262. N3F123 / F196 / P246

- 263. N3F125 / F197 / P247

- 264. N3F127 / F198 / P248

- 265. N3F129 / F199 / P249

- 266. N3F131 / F200 / P250

- 267. N3F133 / F202 / P251

- 268. NF135 / F203 / P252

- 269. N3F137 / F204 / P253

- 270. N3F139 / F205 / P254

- 271. N3F141 / F206 / P255

- 272. N3F143 / F205 / P256

- 273. N3F145 / F206 / P257

- 274. N3F147 / F207 / P258

- 275. N3F149 / F208 / P259

- 276. N3F151 / F209 / P260

- 277. N3F151 / P260 verso

- 278. N3F153 / F210 / P261

- 279. N3F155 / F211 / P262

- 280. N3F157 / F212 / P263

- 281. N3F159 / F213 / P264

- 282. N3F161 / F214 / P265

- 283. F161 / P265 verso

- 284. N3F163 / F215 / P266

- 285. N3F165 / F216 / P267

- 286. N3F167 / F217 / P268

- 287. N3F169 / N218 / P269

- 288. N3F170 / P269 verso

- 289. N3F171 / F219 / P270

- 290. N3F173 / F220 / P271

- 291. N3F175 / F221 / P272

- 292. N3F177 / F222 / P273

- 293. N3F179 / F223 / P274

- 294. N3F181 / F224 / P275

- 295. N3F183 / F225 / P276

- 296. N3F185 / F226 / P277

- 297. N3F187 / F227 / P278

- 298. N3F189 / F228 / P279

- 299. N3F191 / F229 / P280

- 300. N3F193 / F230 / P281

- 301. N3F195 / F231 / P282

- 302. N3F197 / F202 / P283

- 303. N3F199 / F203 / P284

- 304. N3F201 / P285

- 305. N5F203 / F205 / P286

- 306. N3F205 / F206 / P287

- 307. N3F207 / F207 / P288

- 308. N3F209 / F208 / P289

- 309. N3F211 / F209 / P290

- 310. N3F213 / F210 / P291

- 311. N3F215 / F211 / P292

- 312. N3F217 / F212 / P293

- 313. N3F219 / F213 / P294

- 314. N3F221 / F214 / P295

- 315. N3F223 / F215 / P296

- 316. N3F225 / F216 / P297

- 317. N3F227 / F217 / P298

- 318. N3F229 / F218 / P299

- 319. N3F231 / F219 / P300

- 320. N3F233 / F220 / P301

- 321. N3F235 / F221 / P302

- 322. N3F237 / F222 / P303

- 323. N3F239 / F223 / P304

- 324. N3F241 / F224 / P305

- 325. N3F243 / F225 / P306

- 326. N3F245 / F226 / P307

- 327. N3F245 / P307 verso

- 328. N3F247 / F227 / P308

- 329. N3F249 / F228 / P309

- 330. N3F251 / F229 / P310

- 331. N3F253 / F230 / P311

- 332. N3F255 / F232 / P312

- 333. N3F257 / F233 / P313

- 334. N3F249 / F234 / P314

- 335. N3F251 / F235 / P315

- 336. N3F253 / F236 / P316

- 337. N3F255 / F237 / P317

- 338. N3F257 / F238 / P318

- 339. N3F259 / F239 / P319

- 340. N3F261 / F240 / P320

- 341. N3F263 / F241 / P321

- 342. N3F265 / F242 / P322

- 343. N3F267 / F243 / P323

- 344. F267 / P323 verso

- 345. N3F269 / F244 / P324

- 346. N3F271 / F245 / P325

- 347. N3F273 / F246 / P326

- 348. N3F275 / F247 / P327

- 349. N3F275 / P327 verso

- 350. N3F277 / F248 / P328

- 351. N3F279 / F249 / P329

- 352. N3F281 / F250 / P330

- 353. N3F283 / F251 / P331

- 354. N3F285 / F251 / P332

- 355. N3F287 / F252 / P333

- 356. N3F289 / F253 / P334

- 357. N3F291 / F254 / P335

- 358. N3F241 / P335 verso

- 359. N3F293 / F255 / Appendix C.336

- 360. N3F295 / F256 / P337

- 361. N3F297 / F257 / P338

- 362. N3F299 / F258 / P339

- 363. N3F301 / F258 / P340

- 364. N3F303 / F259 / P341

- 365. N3F305 / F260 / P342

- 366. N3F307 / F261 / P343

- 367. N3F309 / F262 / P344

- 368. N3F309 /P344 verso

- 369. N3F311 / F263 / P345

- 370. N3F313 / F264 / P346

- 371. N3F315 / F265 / P347

- 372. N3F317 / F266 / P348

- 373. N3F319 / F267 / P349

- 374. N3F321 / F268 / P350

- 375. N3F323 / F269 / P351

- 376. N3F325 / F270 / P352

- 377. N3F271 / P353

- 378. N3F327 / F1 / P354

- 379. N3F329 /P355

- 380. N3F331 / P356

- 381. N3F333 / P357

- 382. N3F335 / P358

- 383. N3F337 / P359

- 384. N3F339 / P360

- 385. N3F253 / verso Berg pg 339

- 386. N3F341 / P361

- 387. N3F343 / P362

- 388. N3F345 / P363

- 389. N3F347 / P364

- 390. N3F349 / P365

- 391. N3F351 / P366

- 392. Appendix A/7

- 393. Appendix A/8

- 394. Appendix A/9

- 395. Appendix A/10

- 396. Appendix A/11

- 397. Appendix A/12

- 398. Appendix A/13

- 399. C/41

- 400. C/42

- 401. C/43

- 402. C/44

- 403. C/156 verso

- 404. C/157 verso

- 405. C/336

- 406. Appendix B

- 407. Albatross Agreement

- 408. DIAL advert