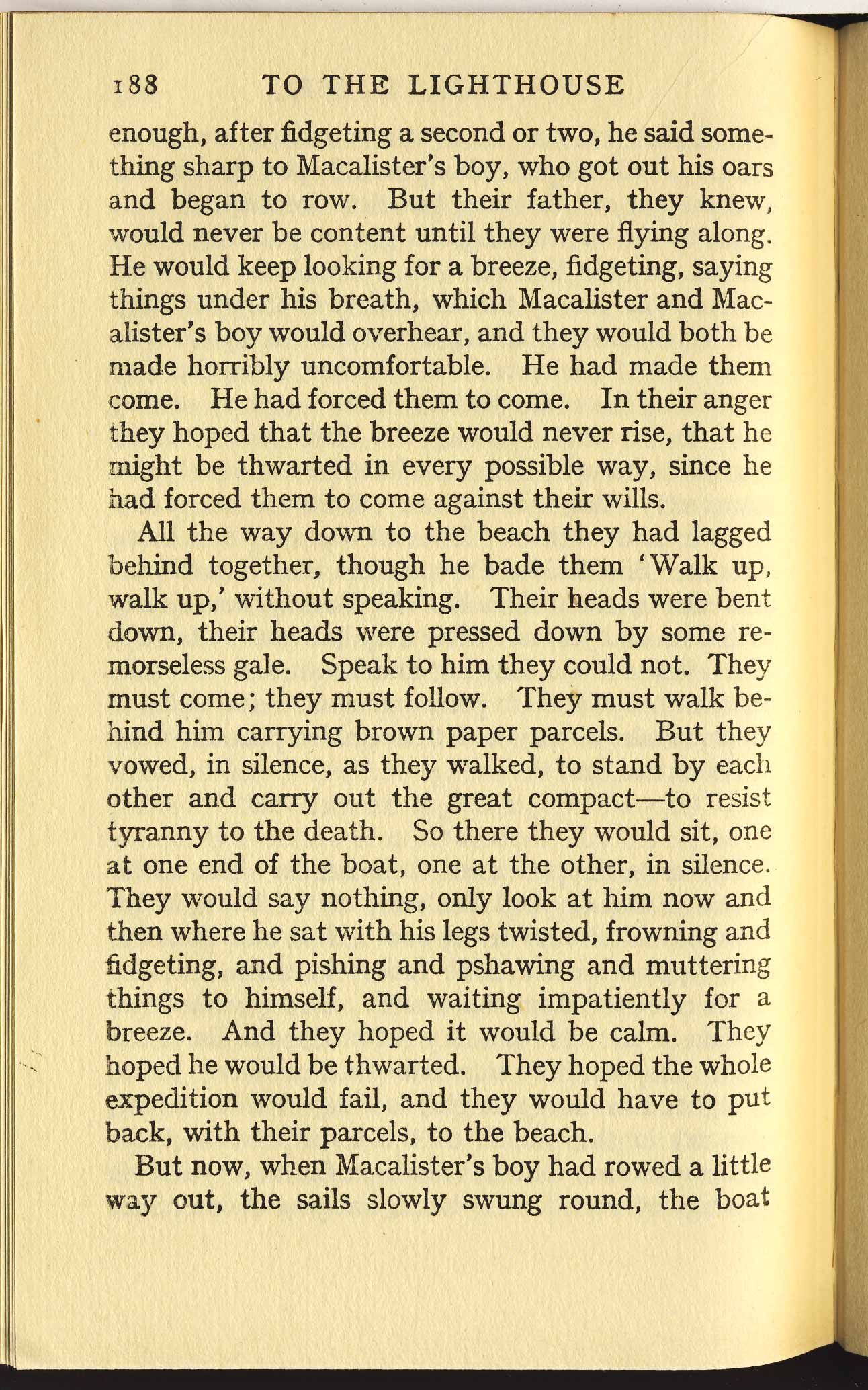

All the way down to the beach they had laggedbehind together, though he bade them ŌĆśWalk up,walk up,ŌĆÖ without speaking. Their heads were bentdown, their heads were pressed down by some re-morseless gale. Speak to him they could not. Theymust come; they must follow. They must walk be-hind him carrying brown paper parcels. But theyvowed, in silence, as they walked, to stand by eachother and carry out the great compactŌĆöto resisttyranny to the death. So there they would sit, oneat one end of the boat, one at the other, in silence.They would say nothing, only look at him now andthen where he sat with his legs twisted, frowning andfidgeting, and pishing and pshawing and mutteringthings to himself, and waiting impatiently for abreeze. And they hoped it would be calm. Theyhoped he would be thwarted. They hoped the wholeexpedition would fail, and they would have to putback, with their parcels, to the beach.

But now, when MacalisterŌĆÖs boy had rowed a littleway out, the sails slowly swung round, the boat

Select Pane

Berg Materials

- 1. Notebook I Cover

- 2. F3 / P1

- 3. F5 / P2

- 4. F7 / P3

- 5. F9 / P4

- 6. F11 / P5

- 7. F13 / P6

- 8. F15 / P7

- 9. F17 / P8

- 10. F19 / P9

- 11. F21 / P10

- 12. F23 / P11

- 13. F25 / P12

- 14. verso of Berg F25

- 15. F27 / P13

- 16. F29 / P14

- 17. F31; P15

- 18. F33 / P16

- 19. F35 / P17

- 20. F37 / P18

- 21. F39 / P19

- 22. F41 / P20

- 23. F43 / P21

- 24. F45 / P22

- 25. F47 / P23

- 26. F49 / P24

- 27. F51 / P25

- 28. F53 / P26

- 29. F55 / P27

- 30. F57 / P28

- 31. F59 / P29

- 32. F61 / P30

- 33. F61 / P30 verso

- 34. F63 / P31

- 35. F65 / P32

- 36. F67 / P33

- 37. F69 / P34

- 38. F71 / P35

- 39. verso F71

- 40. F73 / P36

- 41. F75 / P37

- 42. F77 / P38

- 43. F79 / P39

- 44. F81 / P40

- 45. F91 / P45

- 46. F93 / P46

- 47. F95 / P47

- 48. F97 / P48

- 49. F99 / P49

- 50. F101 / P50

- 51. F103 / P51

- 52. F105 / P52

- 53. F107 / P53

- 54. F109 / P54

- 55. F111 / P55

- 56. F113 / P56

- 57. F115 / P57

- 58. F117 / P58

- 59. F119 / P59

- 60. verso F119

- 61. F121 / P60

- 62. F123 / P61

- 63. F125 / P62

- 64. F127 / P63

- 65. F129 / P64

- 66. F131 / P65

- 67. F133 / P66

- 68. F135 / P67

- 69. F137 / P68

- 70. F139 / P69

- 71. F139 / P69 verso

- 72. F141 / P70

- 73. F143 / P71

- 74. F145 / P72

- 75. F147 / P73

- 76. Fol. 149 / P74

- 77. F151 / P75

- 78. F153 / P76

- 79. F155 / P77

- 80. F157 / P78

- 81. F159 / P79

- 82. F161 / P80

- 83. F163 / P81

- 84. F167 / P82

- 85. 167 / P82 verso

- 86. F169 / P83

- 87. F171 / P84

- 88. F173 / P85

- 89. F175 / P86

- 90. F177 / P87

- 91. F179 / P88

- 92. F181 / P89

- 93. F183 / P90

- 94. F185 / P91

- 95. F187 / P92

- 96. F189 / P93

- 97. F191 / P94

- 98. F193 / P95

- 99. F195 / P96

- 100. F197 / P97

- 101. F197 / P97 verso

- 102. F199 / P98

- 103. F199 / P98 verso

- 104. F201 / P99

- 105. F203 / P100

- 106. F205 / P101

- 107. F207 / P102

- 108. F207 / 102 verso

- 109. F209 / P103

- 110. F211 / P104

- 111. F213 / P105

- 112. F215 / P106

- 113. F217 / P107

- 114. F219 / P108

- 115. F221 / P109

- 116. F223 / P110

- 117. F225 / P111

- 118. F227 / P112

- 119. F229 / P113

- 120. F231 / P114

- 121. F233 / P115

- 122. F235 / P116

- 123. F237 / P117

- 124. F239 / P118

- 125. F241 / P119

- 126. F243 / P120

- 127. F245 / P121

- 128. F247 / P122

- 129. F249 / P123

- 130. F251 / P124

- 131. F251 / P124 verso

- 132. F253 / P125

- 133. F255 / P126

- 134. F257 / P127

- 135. F259 / P128

- 136. F261 / P129

- 137. F263 / P130

- 138. F265 / P131

- 139. F267 / P132

- 140. F269 / P133

- 141. F271 / P134

- 142. F273 / P135

- 143. F275 / P136

- 144. F277 / P137

- 145. F279 / P138

- 146. F281 / P139

- 147. F283 / P140

- 148. F285 / P141

- 149. F287 / P142

- 150. F289 / P143

- 151. F291 / P144

- 152. F293 / P145

- 153. F295 / P146

- 154. F297 / P147

- 155. F299 / P148

- 156. F301 / P149

- 157. F303 / P150

- 158. F305 / P151

- 159. F307 / P152

- 160. F309 / P153

- 161. F311/ P154

- 162. F313 / P155

- 163. 156 verso

- 164. 157 verso

- 165. 158 verso

- 166. Notebook I Rear Cover

- 167. Notebook II Cover

- 168. N2F1 / P159

- 169. N2F3 / P160

- 170. N2F5 / P161

- 171. N2F7 / P162

- 172. N2F9 / P163

- 173. N2F11 / P164

- 174. N2F13 / P165

- 175. N2F15 / P166

- 176. N2F17 / P167

- 177. N2F19 / P168

- 178. N2F21 / P169

- 179. N2F23 / P170

- 180. N2F25 / P171

- 181. N2F27 /P172

- 182. N2F29 / P173

- 183. N2F31 / P174

- 184. N2F33 / P175

- 185. N2F35 / P176

- 186. N2F37 / P177

- 187. N2F39 / P178

- 188. N2F41 / P179

- 189. N2F43 / P180

- 190. N2F45 / P181

- 191. N2F47 / P182

- 192. N2F49 / P183

- 193. N2F51 / P184

- 194. Notebook II Rear Cover

- 195. Notebook III Cover

- 196. N3F1 / P185

- 197. N3F[3] / F138 / P186

- 198. N3F5 / F139 / P187

- 199. N3F7 / F140 / P188

- 200. N3F9 / F141 / P189

- 201. N3F11 / F142 / P190

- 202. N3F13 / F142 / P191

- 203. N3F15 / F143 / P192

- 204. N3F17 / F144 / P193

- 205. N3F19 / F145 / P194

- 206. N3F21 / F146 / P195

- 207. N3F23 / F147 / P196

- 208. N3F25 / F148 / P197

- 209. N3F27 / F149 / P198

- 210. N3F29 / F150 / P199

- 211. N3F31 / F151 / P200

- 212. N3F33 / F152 / P201

- 213. N3F35 / F153 / P202

- 214. N3F37 / F154 / P203

- 215. N3F39 / F155 / P204

- 216. N3F41 / F156 / P205

- 217. verso of VW P156

- 218. N3F43 / F157 / P206

- 219. N3F45 / F158 / P207

- 220. N3F47 / F159 / P208

- 221. N3F49 / F160 / P209

- 222. N3F51 / F161 / P210

- 223. N3F53 / F162 / P211

- 224. N3F55 / F163 / P212

- 225. N3F57 / F164 / P213

- 226. N3F59 / F165 / P214

- 227. N3F61/ F166 / P215

- 228. N3F63 / F167 / P216

- 229. F63 / P216 verso

- 230. NF65 / F168 / P217

- 231. N3F67 / F169 / P218

- 232. N3F69 / F170 / P219

- 233. 219 verso

- 234. N3F71 / F171 / P220

- 235. N3F73 / F172 / P221

- 236. N3F75 / F173 / P222

- 237. N3F77 / F174 / P223

- 238. N3F79 / F175 / P224

- 239. N3F81 / F176 / P225

- 240. 225 verso

- 241. N3F83 / F177 / P226

- 242. N3F85 / F178 / P227

- 243. N3F87 / F179 / P228

- 244. N3F89 / F180 / P229

- 245. 229 verso

- 246. N3F91 / F181 / P230

- 247. N3F93 / F182 / P231

- 248. N3F95 / F183 / P232

- 249. N3F97 / F184 / P233

- 250. F99 / P234

- 251. N3F101 / F185 / P235

- 252. N3F103 / F186 / P236

- 253. N3F105 / F187 / P237

- 254. N3F107 / F188 / P238

- 255. N3F109 / F189 / P239

- 256. N3F111 / F190 / P240

- 257. N3F113 / F191 / P241

- 258. N3F115 / F192 / P242

- 259. N3F117 / F193 / P243

- 260. N3F119 / F194 / P244

- 261. N3F121 / F195 / P245

- 262. N3F123 / F196 / P246

- 263. N3F125 / F197 / P247

- 264. N3F127 / F198 / P248

- 265. N3F129 / F199 / P249

- 266. N3F131 / F200 / P250

- 267. N3F133 / F202 / P251

- 268. NF135 / F203 / P252

- 269. N3F137 / F204 / P253

- 270. N3F139 / F205 / P254

- 271. N3F141 / F206 / P255

- 272. N3F143 / F205 / P256

- 273. N3F145 / F206 / P257

- 274. N3F147 / F207 / P258

- 275. N3F149 / F208 / P259

- 276. N3F151 / F209 / P260

- 277. N3F151 / P260 verso

- 278. N3F153 / F210 / P261

- 279. N3F155 / F211 / P262

- 280. N3F157 / F212 / P263

- 281. N3F159 / F213 / P264

- 282. N3F161 / F214 / P265

- 283. F161 / P265 verso

- 284. N3F163 / F215 / P266

- 285. N3F165 / F216 / P267

- 286. N3F167 / F217 / P268

- 287. N3F169 / N218 / P269

- 288. N3F170 / P269 verso

- 289. N3F171 / F219 / P270

- 290. N3F173 / F220 / P271

- 291. N3F175 / F221 / P272

- 292. N3F177 / F222 / P273

- 293. N3F179 / F223 / P274

- 294. N3F181 / F224 / P275

- 295. N3F183 / F225 / P276

- 296. N3F185 / F226 / P277

- 297. N3F187 / F227 / P278

- 298. N3F189 / F228 / P279

- 299. N3F191 / F229 / P280

- 300. N3F193 / F230 / P281

- 301. N3F195 / F231 / P282

- 302. N3F197 / F202 / P283

- 303. N3F199 / F203 / P284

- 304. N3F201 / P285

- 305. N5F203 / F205 / P286

- 306. N3F205 / F206 / P287

- 307. N3F207 / F207 / P288

- 308. N3F209 / F208 / P289

- 309. N3F211 / F209 / P290

- 310. N3F213 / F210 / P291

- 311. N3F215 / F211 / P292

- 312. N3F217 / F212 / P293

- 313. N3F219 / F213 / P294

- 314. N3F221 / F214 / P295

- 315. N3F223 / F215 / P296

- 316. N3F225 / F216 / P297

- 317. N3F227 / F217 / P298

- 318. N3F229 / F218 / P299

- 319. N3F231 / F219 / P300

- 320. N3F233 / F220 / P301

- 321. N3F235 / F221 / P302

- 322. N3F237 / F222 / P303

- 323. N3F239 / F223 / P304

- 324. N3F241 / F224 / P305

- 325. N3F243 / F225 / P306

- 326. N3F245 / F226 / P307

- 327. N3F245 / P307 verso

- 328. N3F247 / F227 / P308

- 329. N3F249 / F228 / P309

- 330. N3F251 / F229 / P310

- 331. N3F253 / F230 / P311

- 332. N3F255 / F232 / P312

- 333. N3F257 / F233 / P313

- 334. N3F249 / F234 / P314

- 335. N3F251 / F235 / P315

- 336. N3F253 / F236 / P316

- 337. N3F255 / F237 / P317

- 338. N3F257 / F238 / P318

- 339. N3F259 / F239 / P319

- 340. N3F261 / F240 / P320

- 341. N3F263 / F241 / P321

- 342. N3F265 / F242 / P322

- 343. N3F267 / F243 / P323

- 344. F267 / P323 verso

- 345. N3F269 / F244 / P324

- 346. N3F271 / F245 / P325

- 347. N3F273 / F246 / P326

- 348. N3F275 / F247 / P327

- 349. N3F275 / P327 verso

- 350. N3F277 / F248 / P328

- 351. N3F279 / F249 / P329

- 352. N3F281 / F250 / P330

- 353. N3F283 / F251 / P331

- 354. N3F285 / F251 / P332

- 355. N3F287 / F252 / P333

- 356. N3F289 / F253 / P334

- 357. N3F291 / F254 / P335

- 358. N3F241 / P335 verso

- 359. N3F293 / F255 / Appendix C.336

- 360. N3F295 / F256 / P337

- 361. N3F297 / F257 / P338

- 362. N3F299 / F258 / P339

- 363. N3F301 / F258 / P340

- 364. N3F303 / F259 / P341

- 365. N3F305 / F260 / P342

- 366. N3F307 / F261 / P343

- 367. N3F309 / F262 / P344

- 368. N3F309 /P344 verso

- 369. N3F311 / F263 / P345

- 370. N3F313 / F264 / P346

- 371. N3F315 / F265 / P347

- 372. N3F317 / F266 / P348

- 373. N3F319 / F267 / P349

- 374. N3F321 / F268 / P350

- 375. N3F323 / F269 / P351

- 376. N3F325 / F270 / P352

- 377. N3F271 / P353

- 378. N3F327 / F1 / P354

- 379. N3F329 /P355

- 380. N3F331 / P356

- 381. N3F333 / P357

- 382. N3F335 / P358

- 383. N3F337 / P359

- 384. N3F339 / P360

- 385. N3F253 / verso Berg pg 339

- 386. N3F341 / P361

- 387. N3F343 / P362

- 388. N3F345 / P363

- 389. N3F347 / P364

- 390. N3F349 / P365

- 391. N3F351 / P366

- 392. Appendix A/7

- 393. Appendix A/8

- 394. Appendix A/9

- 395. Appendix A/10

- 396. Appendix A/11

- 397. Appendix A/12

- 398. Appendix A/13

- 399. C/41

- 400. C/42

- 401. C/43

- 402. C/44

- 403. C/156 verso

- 404. C/157 verso

- 405. C/336

- 406. Appendix B

- 407. Albatross Agreement

- 408. DIAL advert