Is Fiction an Art?

ASPECTS OF FICTION.

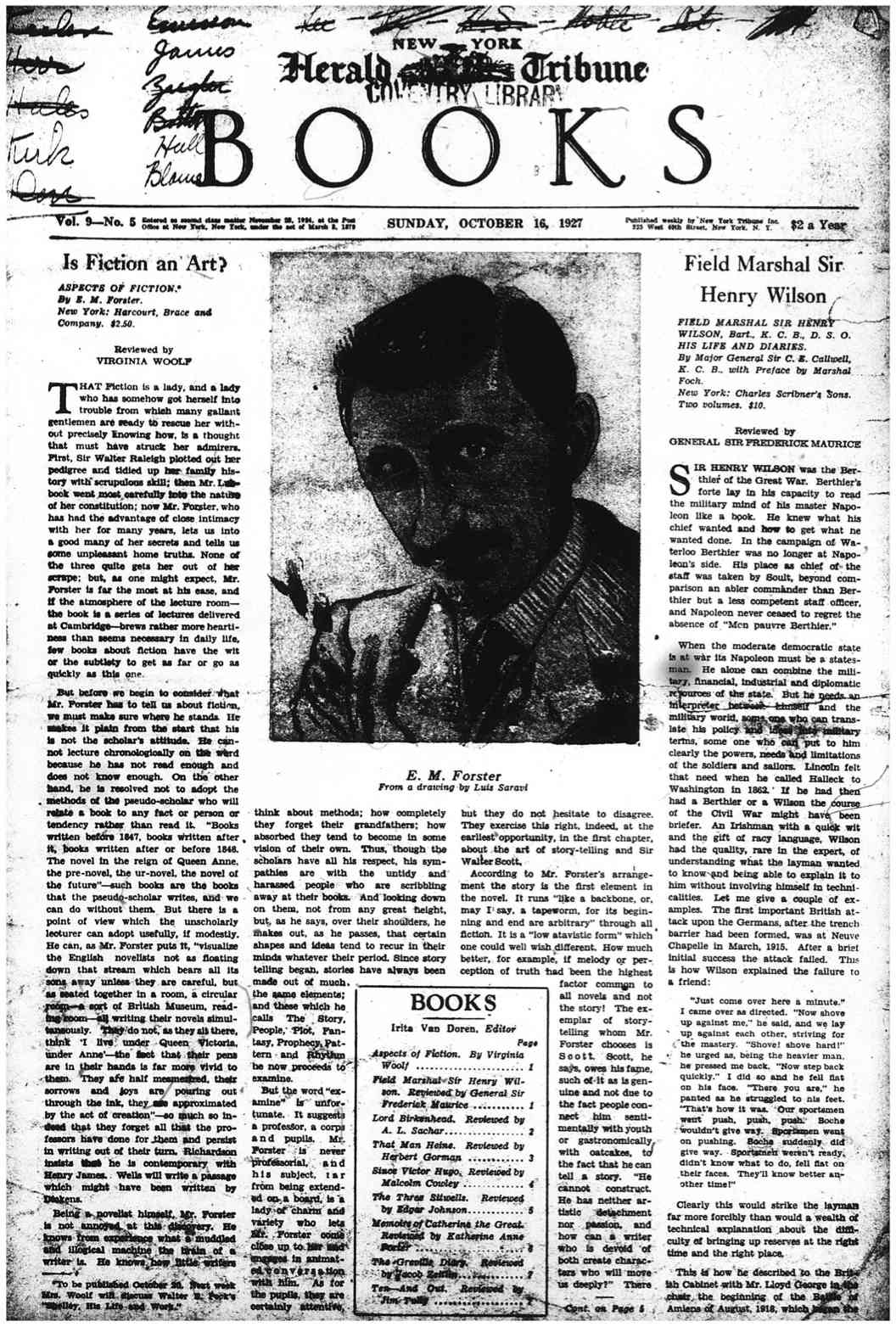

By E. M. Forster

New York: Harcourt, Brace and

Company. $2.50

Reviewed by

VIRGINIA WOOLF

THAT fiction is a lady, and a lady

who has somehow got herself into

trouble from which many gallant

gentlemen are ready to rescue her with-

out precisely knowing how, is a thought

that must have struck her admirers.

First, Sir Walter Raleigh plotted out her

pedigree and tidied up her family his-

tory with scrupulous skill; then Mr. Lub-

bock went most carefully into the nature

of her constitution; now Mr. Forster, who

has had the advantage of close intimacy

with her for many years, lets us into

a good many of her secrets and tells us

some unpleasant home truths. None of

the three quite gets her out of her

scrape; but, as one might expect, Mr.

Forster is far the most at his ease, and

if the atmosphere of the lecture roomŌĆö

the book is a series of lectures delivered

at CambridgeŌĆöbrews rather more hearti-

ness than seems necessary in daily life,

few books about fiction have the wit

or the subtlety to get as far or go as

quickly as this one.

But before we begin to consider what

Mr. Forster has to tell us about fiction,

we must make sure where he stands. He

makes it plain from the start that his

is not the scholarŌĆÖs attitude. He can-

not lecture chronologically on the word

because he has not read enough and

does not know enough. On the other

hand, he is resolved not to adopt the

methods of the pseudo-scholar who will

relate a book to any fact or person or

tendency rather than read it. ŌĆ£Books

written before 1847, books written after

it, books written after or before 1848.

The novel in the reign of Queen Anne,

the pre-novel, the ur-novel, the novel of

the futureŌĆØŌĆösuch books are the books

that the pseudo-scholar writes, and we

can do without them. But there is a

point of view which the unscholarly

lecturer can adopt usefully, if modestly.

He can, as Mr. Forster puts it, ŌĆ£visualize

the English novelists not as floating

down that stream which bears all its

sons away unless they are careful, but

as seated together in a room, a circular

roomŌĆöa sort of British Museum, read-

ing roomŌĆöall writing their novels simul-

taneously. They do not, as they sit there,

think ŌĆśI live under Queen Victoria,

under AnneŌĆÖŌĆöthe fact that their pens

are in their hands is far more vivid to

them. They are half mesmerized, their

sorrows and joys are pouring out

through the ink, they are approximated

by the act of creationŌĆØŌĆöso much so in-

deed that they forget all that the pro-

fessors have done for them and persist

in writing out of their turn. Richardson

insists that he is contemporary with

Henry James. Wells will write a passage

which might have been written by

Dickens.

Being a novelist himself, Mr. Forster

is not annoyed at this discovery. He

knows from experience what a muddled

and illogical machine the brain of a

writer is. He knows how little writers

____

*To be published October 20. Next week

Mrs. Woolf will discuss Walter E. PeckŌĆÖs

ŌĆ£Shelley, His Life and Work.ŌĆØ

[new column]

think about methods; how completely

they forget their grandfathers; how

absorbed they tend to become in some

vision of their own. Thus, though the

scholars have all his respect, his sym-

pathies are with the untidy and

harassed people who are scribbling

away at their books. And looking down

on them, not from any great height,

but, as he says, over their shoulders, he

makes out, as he passes, that certain

shapes and ideas tend to recur in their

minds whatever their period. Since story

telling began, stories have always been

made out of much

the same elements;

and these which he

calls The Story,

People, Plot, Fan-

tasy, Prophecy, Pat-

tern and Rhythm

he now proceeds to

examine.

But the word ŌĆ£ex-

amineŌĆØ is unfor-

tunate. It suggests

a professor, a corps

and pupils. Mr.

Forster is never

professorial, and

his subject, far

from being extend-

ed on a board, is a

lady of charm and

variety who lets

Mr. Forster come

close up to her and

engages in animat-

ed conversation

with him. As for

the pupils, they are

certainly attentive,

[new column]

but they do not hesitate to disagree.

They exercise this right, indeed, at the

earliest opportunity, in the first chapter,

about the art of story-telling and Sir

Walter Scott.

According to Mr. ForsterŌĆÖs arrange-

ment the story is the first element in

the novel. It runs ŌĆ£like a backbone, or,

may I say, a tapeworm, for its begin-

ning and end are arbitraryŌĆØ through all

fiction. It is a ŌĆ£low atavistic formŌĆØ which

one could well wish different. How much

better, for example, if melody or per-

ception of truth had been the highest

factor common to

all novels and not

the story! The ex-

emplar of story-

telling whom Mr.

Forster chooses is

Scott. Scott, he

says, owes his fame,

such of it as is gen-

uine and not due to

the fact people con-

nect him senti-

mentally with youth

or gastronomically

with oatcakes, to

the fact that he can

tell a story. ŌĆ£He

cannot construct.

He has neither ar-

tistic detachment

nor passion, and

how can a writer

who is devoid of

both create charac-

ters who will move

us deeply?ŌĆØ There

___

Cont. on Page 5